In analyzing targeted attacks over the past decade, we continually find a recurring theme: “It all started when the victim opened a phishing e-mail.” Why are spear-phishing e-mails so effective? It’s because they are contextualized and tailored to the specific victim.

Victims’ social networks are often used as a source of information. Naturally, that leads to the question: How? How do cybercriminals find these accounts? To a large extent, it depends on how public the victim is. If someone’s data is published on a corporate website, perhaps with a detailed biography and a link to a LinkedIn profile, it’s quite simple. But if the only thing the cybercriminal has is an e-mail address, the task is far more complicated. And if they just took a picture of you entering the office of the target company, their chances of finding your profile in social networks are even lower.

We conducted a small experiment to search for information based on scraps of data. This involved taking several colleagues, all with varying degrees of social media activity, and trying to find them using widely available search tools.

Search by photo

Needing to find a person based on a photo is not the most common scenario. We assume that it begins with the cybercriminal was positioned by the entrance to the target company building and covertly photographing everyone with a particular logo on their pass, after which the search commenced for a suitable spear-phishing victim. But where to begin?

Two years ago (how time flies), we wrote about the FindFace service. Given certain conditions and the availability of several high-quality pics of a mark, the service can quickly match the image to a social media account. That said, since July of last year, the service has been inaccessible to the casual user. Its creators have been busy developing solutions for government and business, and now it is a fee-based service. Moreover, the creators said straight out that the public version was only a “demonstrator of possibilities.”

However, the service should not be completely discounted. Sometimes cybercriminals are prepared to invest in additional tools to carry out a targeted attack. It all depends on the objective, although this option is bound to leave unwanted traces.

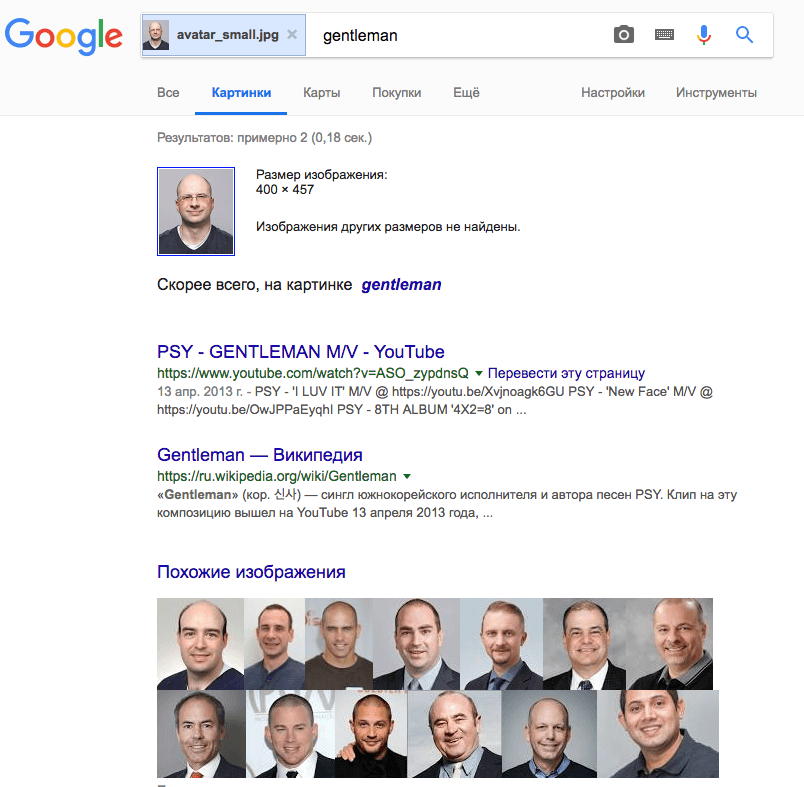

Search by photo is freely available as a service from Google, which also offers a search-by-photo browser extension that automatically scours various search services for photos. However, this method works only for photos already published online. So it is not applicable in our scenario — unless it’s an official photo from a website, but they are rarely published without additional information (first and last name).

Nevertheless, we tried the search option. Google managed only to narrow down our volunteer to “gentleman,” even though he uses the same photo as an avatar in Facebook and other social networks. So, having taken a picture of you, we think cybercriminals are unlikely to match it to your profile without using a paid facial recognition service.

First and last name

When looking for someone online, the first step is usually to do a search on their first and last names. Obviously, the success of the search is highly dependent on the prevalence of the name. Locating a specific John Smith might not be an easy task. But someone with the surname “Lurie” (not the rarest, but still not a common surname), Google finds quite quickly.

By the way, did you know that some social networks let you see a person’s profile without having to register?

E-mail and phone number

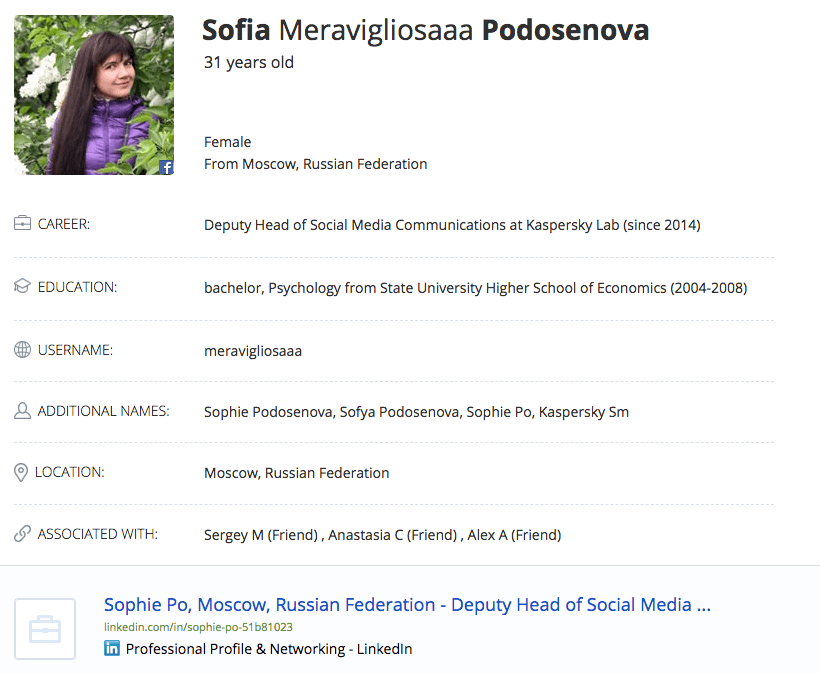

What if we know a person’s e-mail or phone number? Armed with this information, we can take a direct route and search the social networks one by one. But there are aggregator services that automatically harvest the data required, the most popular being Pipl, which can find links to user pages in social networks by phone number or e-mail address, and provide a brief biography, including place of birth, study, and work. If you believe Pipl’s developers, the service has information on more than 3 billion people!

Using this service, we obtained a link to at least one user account for five of our ten subjects, and in some cases even got hold of an online nickname or handle.

Handle

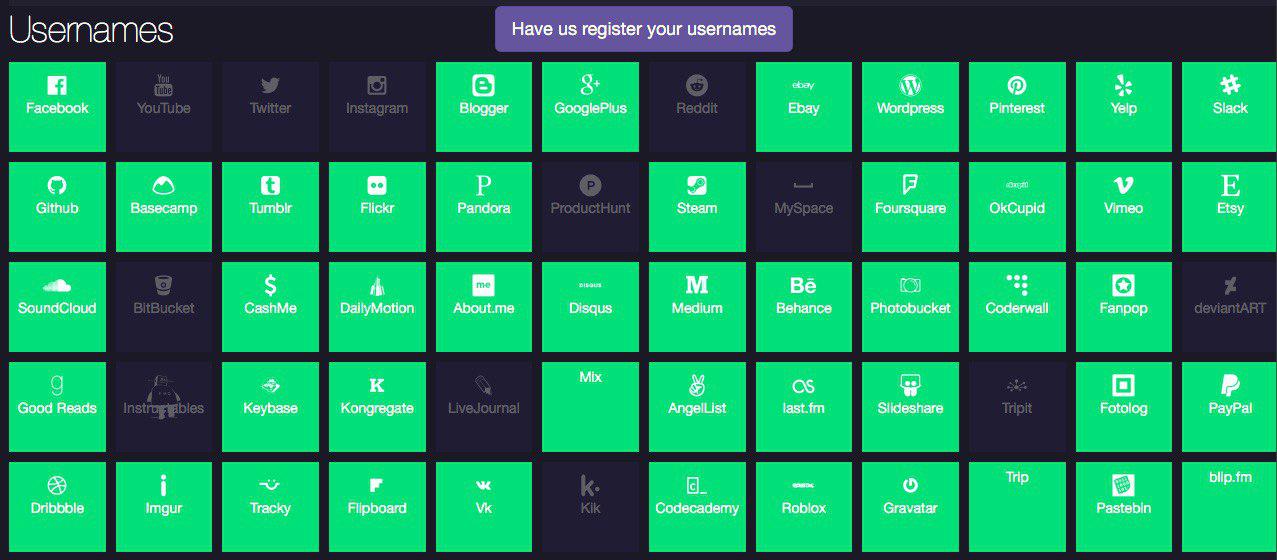

Some people use a single handle for both personal and corporate e-mail addresses; others use one handle for their private online life and also have a corporate address. In the hands of cybercriminals, any handle can be used to extract even more information about the intended victim.

This can be done using resources like namechk or knowem. The former can locate an account name in more than 100 services; the latter checks more than 500 resources. Sure, if the handle is somewhat common, there is no guarantee of finding a specific individual. Even so, such a service is a very handy tool for cybercrooks.

What to do

As you can see, collecting data about potential victims (where they live, what they enjoy, etc.) does not require any technical wizardry or access to complex services. So in addition to reading up on phishing methods, we advise you to recommend a few simple rules for employees:

- Do not register on social networks by e-mail or phone number that are then made public.

- Do not use the same photo for personal profiles and work accounts.

- Use different handles so that knowing one profile does not lead anyone to another.

- Do not make life easier for cybercriminals by publishing unnecessary information about yourself in social networks.

And most important of all, employee workstations should be protected by a reliable, full-featured security solution with effective antiphishing technology — something like Kaspersky Endpoint Security for Business.

phishing

phishing

Tips

Tips