In the new installment of our explosive hit series “Infosec news”:

- The breach of Bugzilla serves a harsh reminder of the necessity to make passwords BOTH strong and unique.

- The Carbanak campaign which allowed the attackers to steal millions of dollars from financial organizations has resurfaced in Europe and USA.

- The research by Kaspersky Lab finds the method of enhancing the level of cyberespionage C&C server secrecy from ‘very hard to track’ to ‘Level-God hard to track’.

Once again, the rules of the road: every week the editorial team at Threatpost hand picks three top news which I ruthlessly comment.

The breach of the Bugzilla bug database

Last week’s installment issue, I raised the question of responsible disclosure and listed cases when it’s desirable/undesirable to disclose the information about the bugs one could discover. The story about Mozilla’s bug tracker breach serves a perfect example when the vulnerability would have been better not disclosed.

Attacker Compromised #Mozilla Bug System, Stole Private Vulnerability Data: https://t.co/FyAMl8wUyB via @threatpost pic.twitter.com/yXThX1mBlC

— Kaspersky (@kaspersky) September 8, 2015

It’s clear that the issue has not been fixed yet. Back in August Mozilla issued a patch for Firefox which closed the bug in the built-in PDF Viewer. The bug was discovered by a user who fell victim of the exploitation and then reported the vulnerability. The entry point for the attack was a specially crafted banner which allowed a culprit to steal the user’s personal data.

I have a notion that while the developers were preparing the patch, they were already aware of the bug. Bugzilla already contained the information on the bug, although it was stored in the private part of the system. Then suspicions arose about illegitimate access and those were proven to be true last week. There was no ‘breach’ as such: the attackers identified a privileged user, found his password in another compromised database – and the password happened to match with the Bugzilla password.

As a result, the attackers had access to the secret bug database starting from as early as September 2013. During this period, as noted in a very detailed FAQ on the attack, the hackers had access to the information on 185 bugs, 53 of them critical. Forty-three vulnerabilities from the compromised list had been patched by the time the culprits accessed the database.

From the remaining bugs, information on two of them is likely to have leaked less than a week before having been patched; five, in theory, could have been exploited during a week up to a month before the patch became available. The remaining three vulns could have been used 131, 157, and 335 days before the patch was out. That was the most dreadful news about the breach; however, Mozilla’s developers don’t have any ‘proof that those vulnerabilities have in fact been exploited.’ From over 50 bugs, only one has been used itw.

How strong is your #password? Check it here: http://t.co/9ILaxq503k https://t.co/P9Pm0SGc4n #internet #security #infosec

— Kaspersky (@kaspersky) August 21, 2015

Well, the moral here is simple, and this is when I feel an urge to climb on some improvised stage and proclaim: “Friends! Brothers and Sisters! Ladies and Gentlemen! Please use a unique password for each separate service!” However, that is not as simple as it seems: such an approach would definitely require a password manager. Even if you already have it, you have to sit down and accurately and thoroughly change passwords on all resources you actively use, ideally, on all of them. Our data proves that only 7% of people use password managers.

New Carbanak versions attack USA and Europe

News. The February research by Kaspersky Lab. A newer research by CSIS.

Let me quote the announcement on ‘the great theft’ we made back in February:

“The attackers were able to transfer money to their own bank accounts and manipulate the balance report in the manner which prevented the attack to be discovered by a number of robust security systems. This operation would have never succeeded if not for the control of the culprits over the banks’ internal systems. That’s why after the breach the culprits used a number of intelligence techniques to gather the necessary information about the way a bank infrastructure works, including video capture”.

In a joint effort with the law enforcement organizations it was discovered that the loss the banks sustained as a result of the complex, multilayer Carbanak attack totaled a billion dollars, with over a hundred of large financial institutions being victims. But it happened back in February, and in the end of August the researchers of Denmark’s CSIS discovered a new modification of Carbanak.

The differences between the new and the old versions are not significant: one of them is the use of a static IP address for C&C communication instead of a domain name. As for plugins used for the data theft, they are identical to those used back in February.

In what may be the greatest heist of the century, hackers steal billions from hundreds of banks: http://t.co/W3CofvF5ta

— Kaspersky (@kaspersky) February 16, 2015

According to CSIS, the new version of Crabanak was targeting large companies in Europe and US.

Turla APT: how to hide C&C with the help of satellite Internet

The Turla APT cyberespionage campaign has long been studied by various infosec researchers, including those of Kaspersky Lab. Last year we published a very detailed research on the methods of breaching into the victim’s computers, gathering data and sending it to C&C servers.

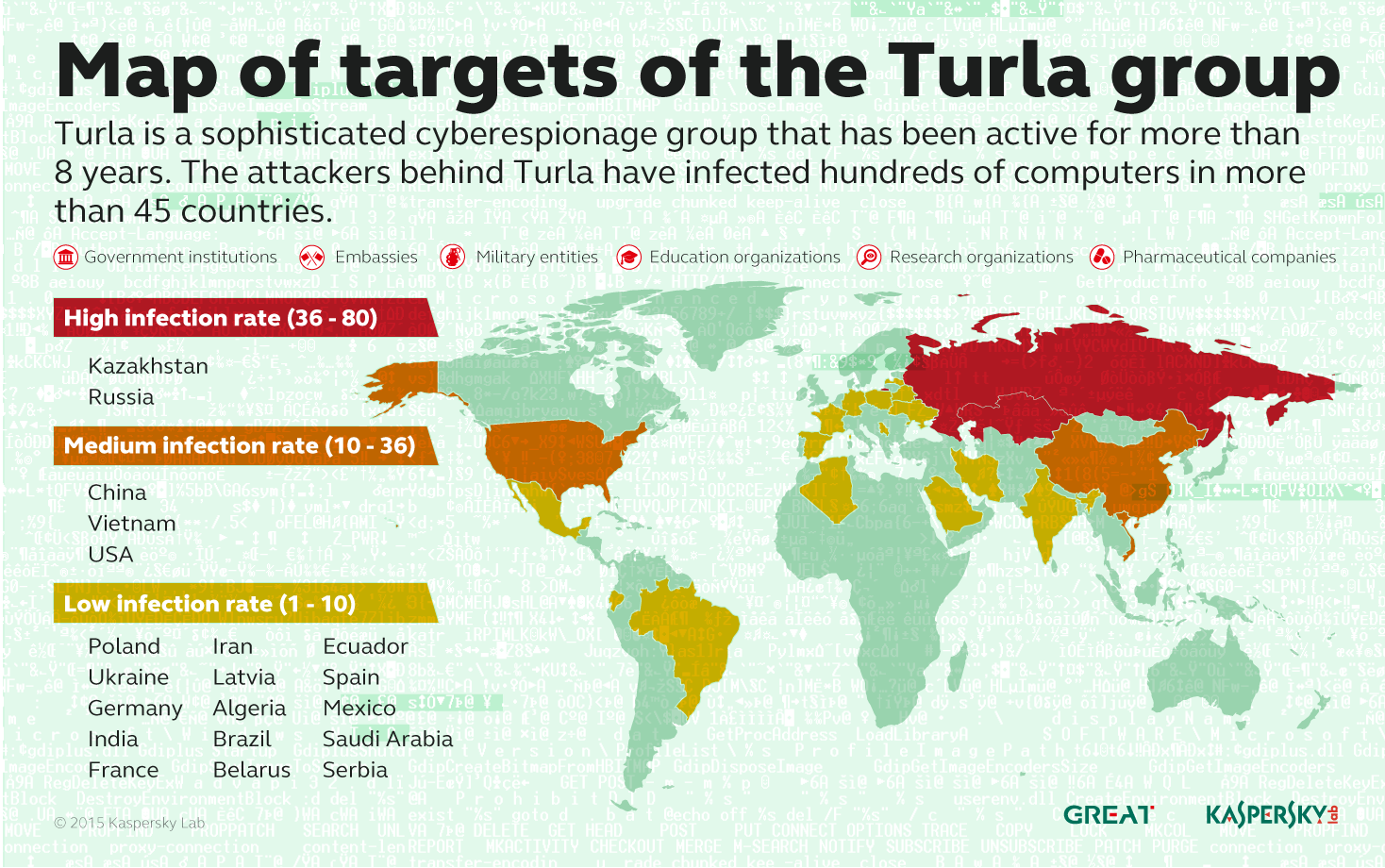

Each of the stages of this complex campaign relies on a number of tools, including spear phishing with infected documents exploiting 0-days; infected websites; various data mining modules hand-picked depending on the complexity of the target and the criticality of the data; and a very advanced network of C&C servers. As a result, by last August, the campaign claimed several hundreds of victims in 45 countries, especially in Europe and Middle East.

RT @threatpost: Agent.btz #Malware May Have Served as Starting Point for Red October, #Turla – http://t.co/6x98OI4afx

— Kaspersky (@kaspersky) March 13, 2014

This week Kaspersky’s researcher Stefan Tanase published the data on the final stage of the attack, when the stolen data is sent to a C&C server. To enable data mining, Turla, as many APT groups before, uses a variety of methods – for instance, abuse-resistant hosting. But as soon as the data in question lands in the particular C&C hosted on a particular server, the likeability of being arrested by law enforcement or blocked by a service provider is quite high, regardless of proxies the culprits might have in place.

And this is when the satellite Internet comes to play. The advantage here is that the server might be established or moved anywhere in the range of the satellite. But there is a rub: in order to lease a bidirectional satellite channel of decent capacity, you need to pay tons of money, and,besides, the paper trail will give you away easily as soon as the trace is found. Well, the method discovered by our researcher does not presuppose a lease model.

There is a thing called “satellite fishing,” a lightly modified piece of software on the satellite terminal does not reject packets which are not intended for a particular user, but collects them. As a result, the “fisher” may gather someone else’s web pages, files, and data. This method is operational under one condition: if the channel is not encrypted.

The Turla attack employs the same method, with one slight modification: when probing the traffic, the attacker should identify the victim’s IP address and make compromised machines send data to this IP belonging to a legitimate, good-willed, unknowing owner of the satellite terminal.

During the attack, the hackers use specific communication ports which are closed by default on average systems and reject the packets by design. But those who probe the traffic might hijack this data without revealing their location.

Russian-speaking cyber spies exploit satellites https://t.co/EIhfVg2aRD #turla pic.twitter.com/b8LTv4t041

— Kaspersky (@kaspersky) September 9, 2015

By the way, old radio phones did not encrypt the voice traffic at all, as the receiving devices able to operate on such frequency bands were quite expensive. It used to be so, but in a matter of no time various all-band receivers started to pop up here and there, priced very moderately.

It’s quite a lousy comparison, as the ‘Turla-designed’ data mining and processing solution would have cost at least a couple of thousands of dollars. But the bottom line is that satellite Internet systems have an inherent flaw leveraged by attackers. There is no action plan on closing this vulnerability, and the outcome remains unclear.

As a result, the approximate location of Turla’s C&C server coincides with the range of the satellite operator:

And here we lose the trace.

What else happened:

Another type of Android ransomware was found. It communicates with C&C server via XMPP. Chats and other instant messengers have been already used for communication by various PC malware, so the news proves that mobile malware is following the same path of progress as desktop malware, only a lot faster.

#mobile #malware New Android Ransomware Communicates over XMPP: https://t.co/NaduU8sGbH via @threatpost pic.twitter.com/j3sG6zS7xc

— Kaspersky (@kaspersky) September 3, 2015

Another series of patches for critical vulns in Google Chrome were published (we advise you to update your browser and setup V45).

Seagate’s wireless hard drives happened to contain a couple of serious bugs: unencrypted access via telnet and a hard-coded password for root access. This is quite critical, but we discussed this topic last week when talking about routers. The morale: everything which seeds Wi-Fi should be heavily protected. In today’s reality, everything can seed Wi-Fi, ever cameras.

Oldies:

Manowar-273

A harmless resident virus which typically plagues .COM and .EXE files when they are run (the COMMAND.COM files is infected by the Lehigh algorithm). The virus contains the text: “Dark Lord, I summon thee! MANOWAR”.

Iron-Maiden

A very dangerous non-resident virus which typically infects .COM files of the current catalogue. As of August 1990, depending on timing, might erase two random sectors on hard drives. Contains the text: “IRON MAIDEN”.

Quoted from “Computer viruses in MS-DOS” by Eugene Kaspersky, 1992. Pages 70, 75.

Disclaimer: this column reflects only the personal opinion of the author. It may coincide with Kaspersky Lab position, or it may not. Depends on luck.

APT

APT

Tips

Tips