Phone improvements have long followed a well-trodden path: brighter screen, more memory, better camera, longer battery life. As a result, there’s less and less to get excited about when it comes to product announcements. But in 2022, Apple, Huawei, and Motorola really did unveil something new and unexpected: texting via satellite. It’s not yet about Instagramming from the top of Everest or in the middle of the Pacific, but you can now at least call for help or report your location with neither Wi-Fi nor 4G.

How it works

Satellite phones have been around for three decades, but they are still expensive, inconvenient, and fairly bulky. An innovation of recent years is satellite connectivity on ordinary phones — but this required new satellites. Previously, satellite phones worked using a small number of high-Earth-orbit satellites. But over the past 5–7 years, the key players — Iridium and Globalstar — have launched quite a few low-Earth-orbit (LEO) satellites, operating at an altitude of just 500–800 kilometers. The most hyped project of this kind is undoubtedly Elon Musk’s Starlink. However, while using similar technology, Starlink is aimed at relatively high-speed internet, and requires the subscriber to purchase a special terminal. However, in late December 2022, the first Starlink Gen2 satellite was launched, which will also provide connectivity for regular – non-satellite – smartphones.

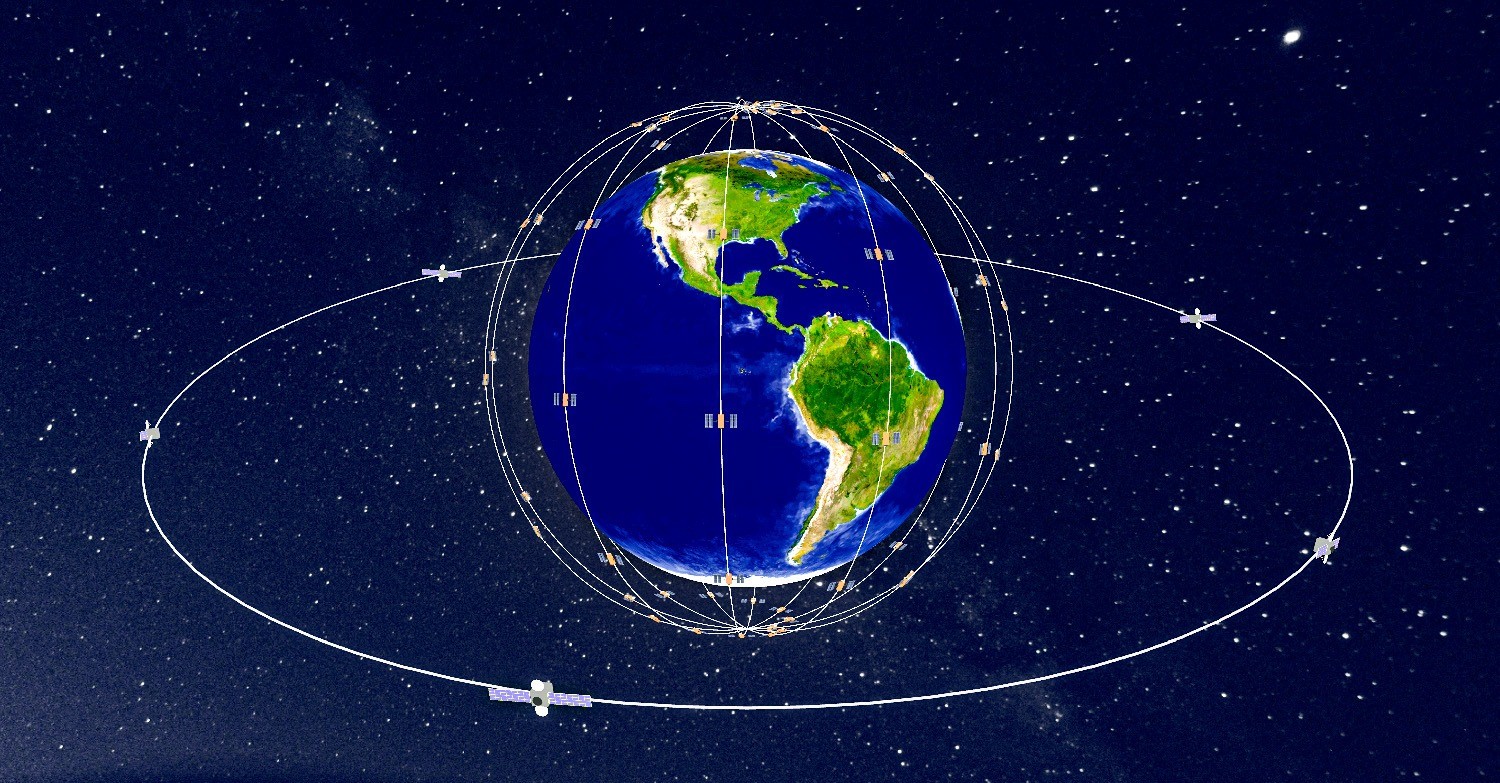

Iridium’s LEO constellation and geostationary satellites of another operator. Illustration from iridium.com

The satellites communicate with a phone in the relatively low-frequency L band (1.5–2 GHz). GPS and GLONASS satellites, which orbit at around 20,000 kilometers above Earth, operate in the same frequency range. The advantages of this range are low levels of both signal decay over long distances and weather interference. Thanks to this, the satellite can “hear” the phone’s weak transmitter. The main disadvantage is a low data-transfer rate. That’s why all satellite-based services we’re discussing today basically rely on the SMS format: 140 characters per message, and not a selfie in sight.

To support satellite communication, three things are required from the phone: modem support for the satellite network radio protocol, a modified antenna, and special software. The trickiest is the first of these, because such a modem needs to not only be produced in the first place, but also coordinated with the satellite operator. Not surprisingly, the leader of the pack is Qualcomm, which not only dominates the mobile chipset market, but also has nearly 30 years of experience in satellite systems (after having jointly founded the Globalstar network in 1994). Therefore, the first large-scale launch of satellite telephone communication was made possible by Qualcomm’s knowhow and Apple’s financial muscle. The latter paid for the feature to be implemented in the new iPhone chips, and, more significantly, invested a solid US$450 million in the development of the Globalstar network, its satellites and ground stations.

Apple was the first to enter the market, but for sure won’t remain the monopolist. At the same time, Qualcomm has implemented the feature in its Snapdragon X70 modem chip, which is part of the flagship Snapdragon 8 Gen 2 Mobile Platform. The Snapdragon Satellite service was announced in partnership with the Iridium network, so in H2 2023 we can expect (expensive) smartphones capable of sending and receiving text messages via satellite.

Other players are scrambling aboard too: Huawei plans to provide a similar service in its smartphones using China’s BeiDou Navigation Satellite System (although there are no details on the timing or coverage); Motorola is partnering up with the Skylo (Inmarsat) satellite provider; and the above-mentioned Starlink has entered into an agreement with U.S. operator T-Mobile to co-deploy such a service on T-Mobile’s licensed 1.9 GHz bands.

For future 5G devices, the ability to communicate with satellite base stations instead of ground ones is already standardized. But actual devices with such functionality are set to appear no earlier than 2024.

Quality and coverage

The technology imposes its own limitations, which will be the same whoever makes the phone.

First, it’s certainly slower and less reliable than cellular communication. Thus, the phone will offer the satellite option only if there’s no other connection available, and with major restrictions so as not to overload the network: one 140-character text and no multimedia — in emergencies, for example. Apple demonstrates this very clearly: first, the phone determines the precise location and asks for a few details about the situation, then it integrates the collected information and sends it as one packet.

Second, the satellite link only works in open spaces. There’s no linkage in thick forest, dense urban areas, or rocky gorges.

Third, sending a text isn’t as simple as we’re used to. You need to: hold the phone in front of you, turn in the right direction, follow the on-screen instructions, and then wait 10–60 seconds until the hundreds of bytes are sent and received.

Fourth, depending on the satellite provider, the service may not be available in certain regions. This is perhaps the biggest drawback at present — the lack of a developed market for either satellite communications or roaming. As such, both Globalstar and Apple offer Emergency SOS in the U.S., southern Canada, and some countries in Western Europe. Satellites do not generally serve high latitudes (above the 62nd parallel), which leaves Alaska and northern Canada, for example, out of reach. The situation with Iridium is better: its satellites work both at the equator and the two poles. The only thing missing is compatible Android terminals from Qualcomm’s partners. Some satellite constellations have gaps in their coverage, so certain places are not served 24/7. This is not relevant for Apple and Qualcomm services, but some competitors may show a “Please try again in half-an-hour” message at the crucial moment.

Prices

No one has any clear idea yet of how much the service should cost. Clearly, it won’t be mass-market, because most people live inside the regular cellular network coverage area. What the surcharge for emergency communications will be, and in what format, the market will test and determine in the coming years. Apple offers it as a free service, but only for two years after purchasing a new iPhone. What the subscription fee will be after that the company hasn’t announced. But usage will be modest, because Apple is positioning the feature solely as an emergency communication channel. All we know for now (at the time of posting this blogpost) is that Motorola plans to charge US$5 for 30 messages. But these can be any messages — not just emergency ones.

Security

Texting is widely known to be an insecure communication channel. So what about the privacy of satellite texts? Apple says its messages are packaged and encrypted, making them near impossible to fake or intercept when sent from a phone to a satellite. However, since they pertain to an emergency, the company immediately forwards the information to the response center closest to the subscriber (rescuers, firefighters, etc.), where it is no longer encrypted and is processed according to that center’s procedures. The same is true for the Snapdragon Satellite service, which relies on Garmin inReach infrastructure: the data transfer itself is encrypted, but the operators then handle the decrypted text. When texting friends, and not the emergency services, don’t count on end-to-end encryption — all specifications only mention in-transit encryption. The good news is that this rules out substitution of the sender address or replacement of the message text.

For a glimpse into what to expect from phones in the foreseeable future, take a look at the ads for the inReach service, for which specialized devices have long been available. Among the potentially unsafe features in terms of privacy is periodic sending of the subscriber’s location to the satellite to enable their friends to track their ascent up a mountain, for example. To date, no service based on conventional smartphones is touting this option — only on-demand sending of location. But given that you have to pull out your smartphone and spin around in search of a satellite, there’s no need to worry about stealthy location sending, at least for now. But it’s worth keeping an eye on the development of this technology.

satellites

satellites

Tips

Tips