Main Findings

- People’s memories are precious, and so is the data that encapsulates those memories. People store this data on their connected devices and carry it around with them: half, for example, store photos and videos of their children on their smartphones (52%) and 59% store this data on their computers.

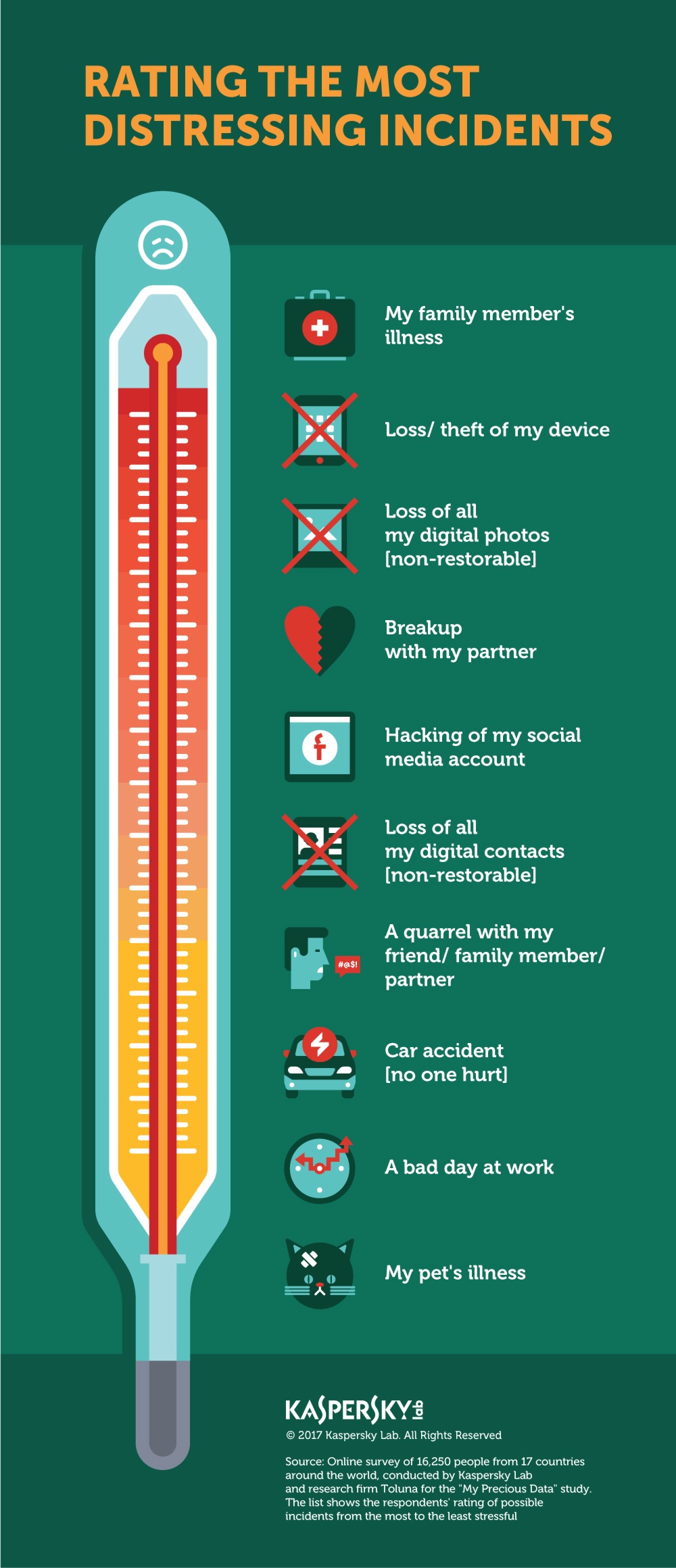

- They rate some data as even more precious than other people: the thought of losing some of the data stored on digital devices is more distressing for people than the prospect of a car accident, a bad day at work, breaking up with a partner, or a quarrel with a friend/ family member or partner.

- When people believe they have lost important data, they show some physical reactions of distress: people demonstrate greater physiological and expressive reactions when they believe they have lost important data, compared to when they believe they have lost trivial data.

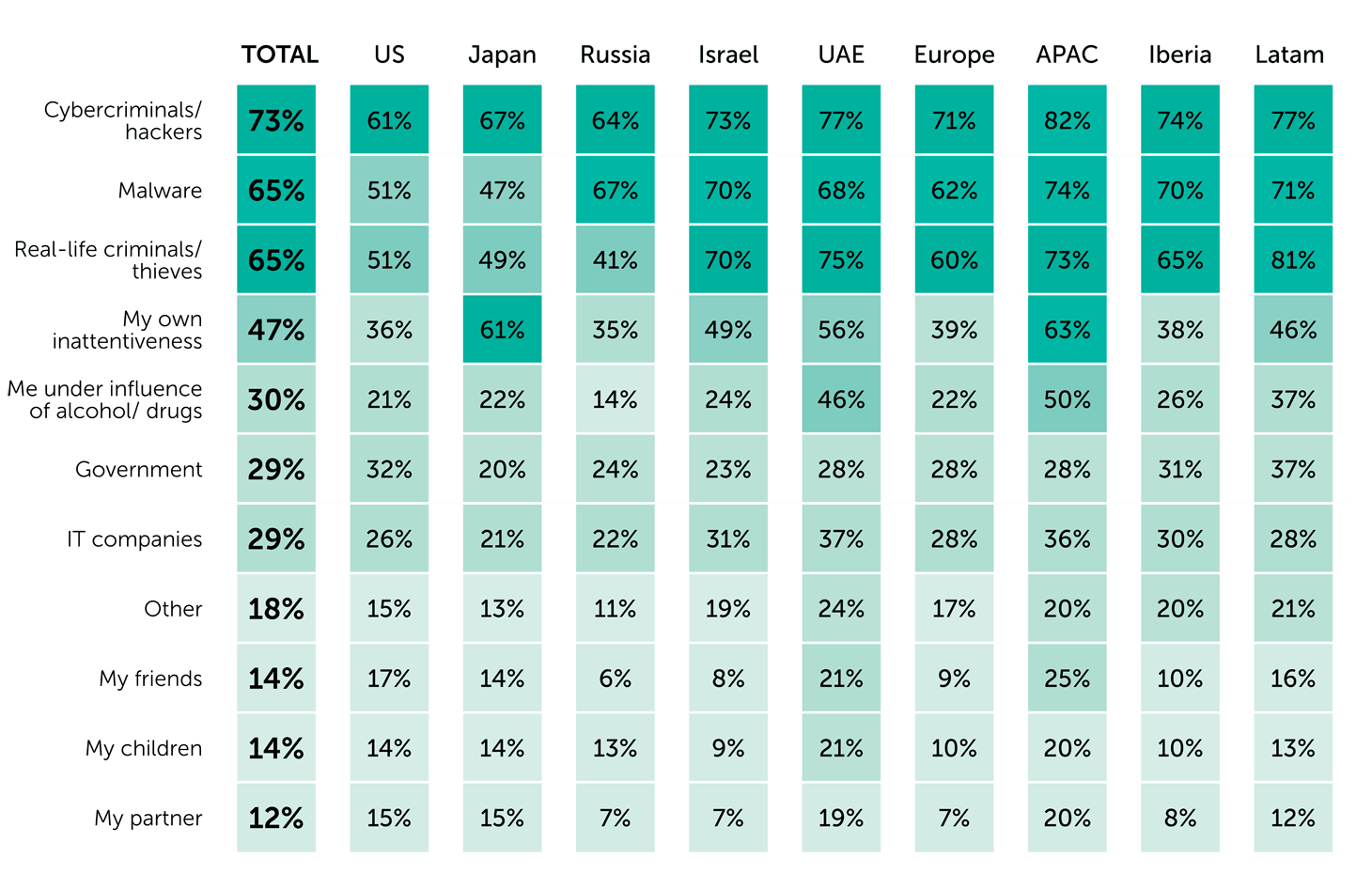

- When it comes to protecting important data from loss or damage, there is an awareness about the dangers data is exposed to: 73% agreed cybercriminals pose a high risk to their data privacy and 65% believe their data is at high risk from real-life criminals and thieves.

- But people are failing to understand the true value of their data, and this is leading to contradictions in people’s behaviour: people put little monetary value on data that they admit they find emotionally distressing to lose. People would be willing to pay just 74.73 € on average to recover all of the data on their smartphones (excluding a small number of people who are willing to pay 500 to 5000 €).

- Photos, surprisingly, are also among the data that is worth the least amount of money to people: despite being some of the most distressing data to lose, people would allow someone else to delete their general photos for just 10.37 € on average and photos of their family and friends for 9.05 € on average.

- Because of this lack of understanding the true value of their data, people put their devices and precious memories in danger: around half do not even use basic security measures such as passwords or PINs to protect their devices and only about a third use a security solution.

- They are therefore at risk of data heartache: 40%, for example, have accidentally deleted data on their smartphones themselves and 47% have lost data by damaging their own smartphones. Only 16% has been able to recover all of their data once it’s been lost.

Introduction

In today’s online world we rely on our digital devices to connect us to the people, memories and information we love. We store photos of our travels, family, friends and children on our devices and we carry these around with us everywhere so they can be shared, observed and treasured.

The prospect of losing these memories is extremely distressing.

Knowing this, and in order to help people protect their precious data, Kaspersky Lab has undertaken this study into the data people love. Using an online survey we asked people difficult questions about what data is important to them, and what data would be upsetting for them to lose. Through a series of experiments at the University of Wuerzburg, Germany, we also asked people to place monetary value on some of their most important data and even measured their physical reactions when we simulated the loss of their data.

The results have been varied and fascinating. We found that despite people being emotionally attached to the data they store on their smartphones, tablets and computers, they are not giving that data the affection and protection it deserves. They are yet to truly understand the value of their data, and take appropriate measures to protect it.

Too much data is left exposed to cybercriminals, or even put in danger through carelessness and lack of protection.

This report discusses the findings of the study and urges people to better protect the data they love — in order to avoid the risk of data heartbreak.

Methodology

This study is based on insight gained from a unique combination of online research and university-led behavioural analysis experiments:

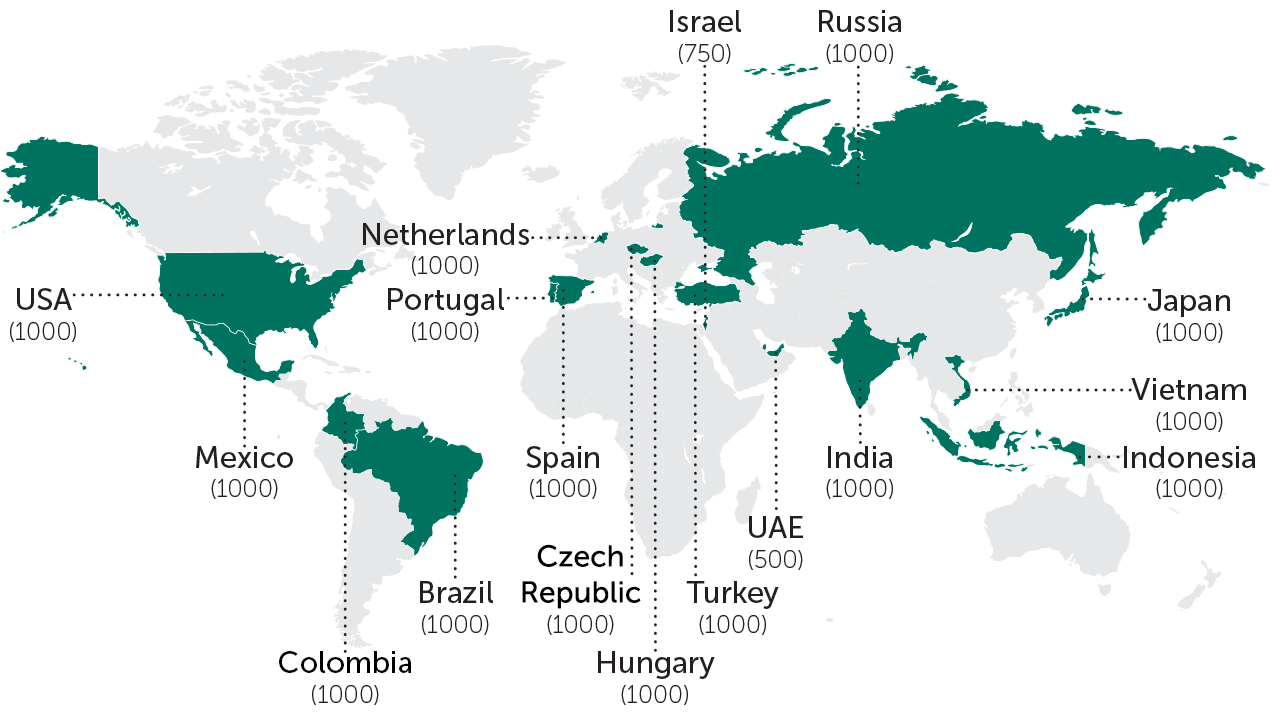

- An online survey conducted by research firm Toluna and Kaspersky Lab in January 2017 assessed the attitudes of 16,250 users aged over 16 years old from 17 countries. Data was weighted to be globally representative and consistent, split equally between men and women.

- A study consisting of two experiments conducted by the University of Wuerzburg, Germany. This study addressed the cognitive component (the monetary value of data) and the emotional processes that occur during data loss. For a full methodology of the experiments please see the report: Lost Data.

Not all the results from each study have been included in this report. To request further data please contact Kaspersky Lab at prhq@kaspersky.com.

The keys to our hearts

These days people use their devices to store data from all aspects of their digital lives — from precious photos, to the contact information that helps us stay in touch with loved ones. In fact, the growing amount of precious data and the amalgamation of applications that we use to store, access, and share that data is leading to high levels of digital clutter (see My Precious Data: Digital Clutter and its Dangers for more information).

We have so much data, and large amounts of digital clutter. But still, the thought of losing some of this data is distressing. At Kaspersky Lab we believe it is important that people understand where their sensitive data is stored, and the dangers it may be in, so that we can help protect it.

Where sensitive data is stored

People tend to keep their most sensitive data on their computers — for example around half of people (48%) keep scans of their passport, driver’s licence, insurance or other sensitive scanned documents on their computers, but only 15% keep this sort of document on their tablets and a quarter (24%) keep them on their smartphones.

Overall, 79% keep all types of documents on their computers, 50% on their smartphones and 35% on their tablets.

This pattern can also be seen with precious memories — such as photos of users, their children or their travels, with more people storing these precious memories on their computers than any other device. 89% store all types of photos on their computers, and 86% also do this on their smartphones, compared to 59% that store all types of photos on their tablets.

But still, a large amount of private information is stored on people’s smartphones. For example, 51% store private and sensitive photos and videos of themselves, and two-fifths (40%) store passwords on their devices.

People love their memories more than other data

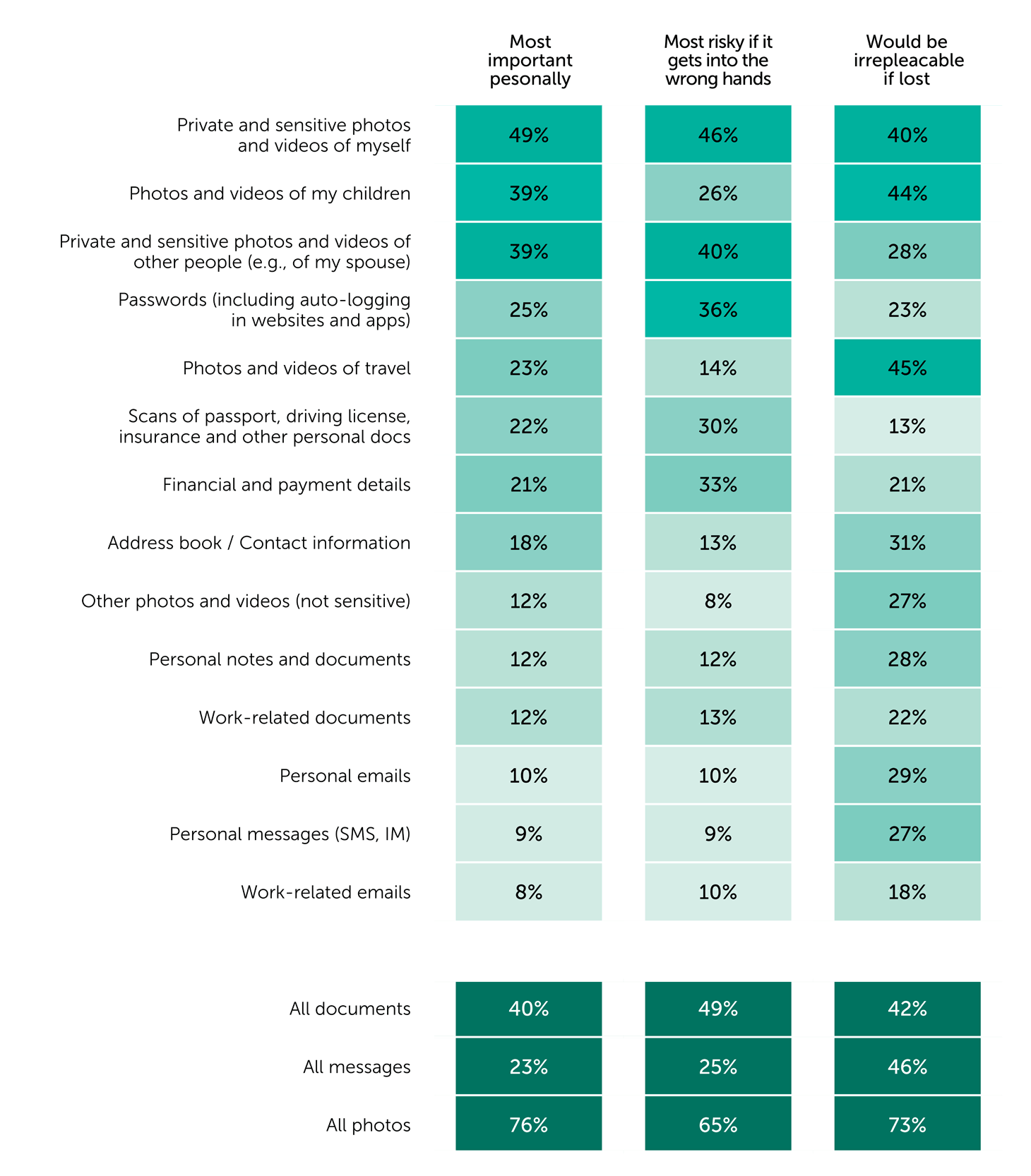

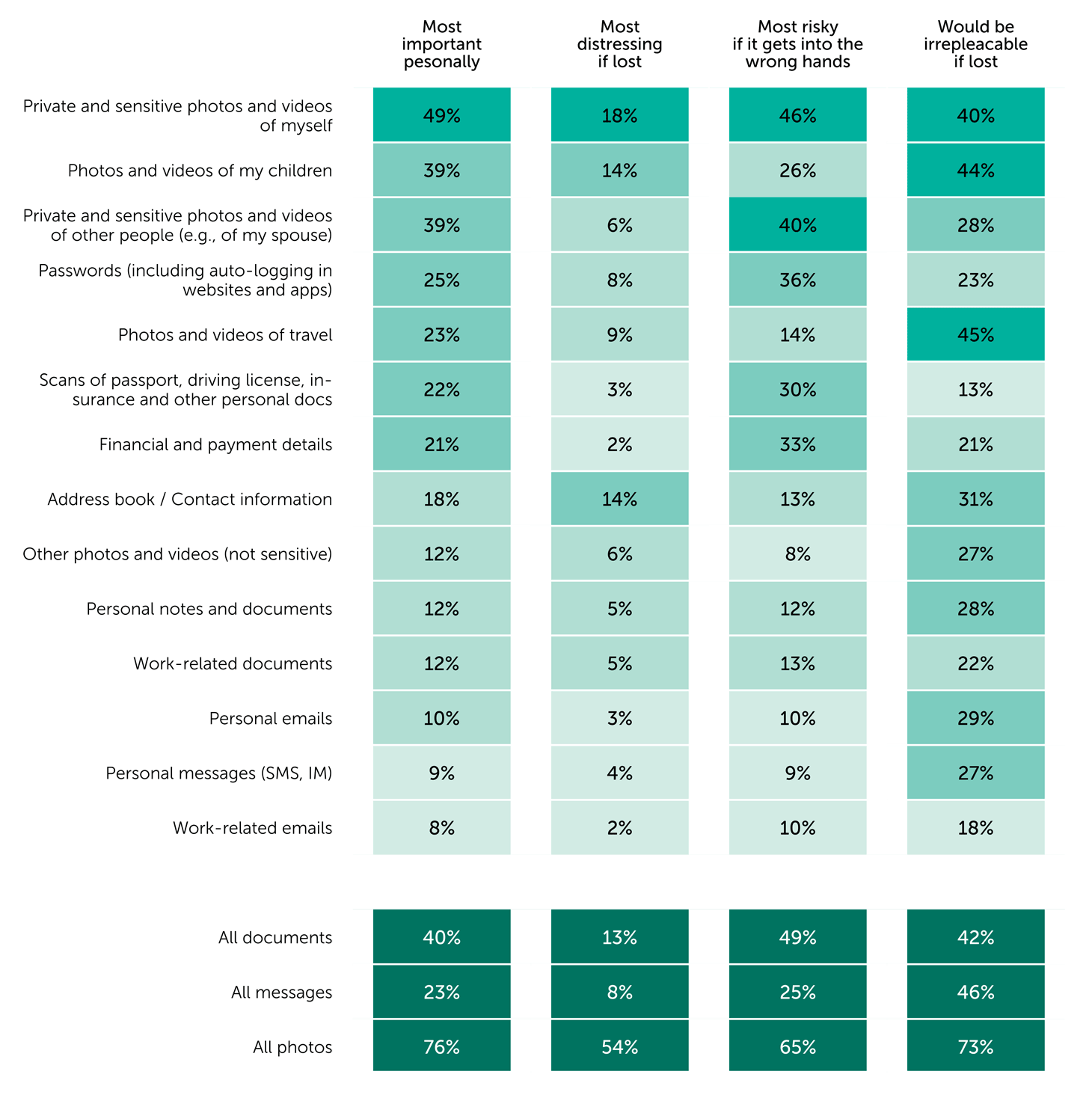

Our studies found that people value their memories more than any other form of data stored on their digital devices. When asked what data was most personally important to them, ‘private and sensitive photos and videos of myself’ emerged as the most loved data (49%). This was followed by ‘photos and videos of my children’ and ‘private and sensitive photos and videos of other people (eg: my spouse).’

Respondents in Japan (36%) and the US (37%) were exceptions to the rule, being the least likely to say private and sensitive photos of themselves were important, compared to the UAE and Russia (59%), APAC (53%) or European (49%) respondents. Respondents in Japan were more likely (47%) to say their passwords were important, than respondents in any other region, perhaps because for a third of people here, their passwords are irreplaceable if lost (34%).

Generally, the study shows us a correlation between data that is important to people, and data that is irreplaceable. We can see that memories have a special place in people’s hearts, and this data is also often irreplaceable. Over two-fifths, for example, say they wouldn’t be able to replace photos and videos of their travels (45%), their children (44%) or themselves (40%). Financial data, by contrast, is viewed as important by fewer people (21%), despite the fact that 33% admit it is ‘risky’ information. Perhaps this is because it can be replaced by banks, and is therefore less distressing to lose.

The data we love the most:

Memories are more important than other people

People do, on the whole, place their memories above other forms of data in importance. In fact, the study shows that people often value their device and photos even more than their partners, friends or pets.

We asked people how distressed they would be in a number of different scenarios, including the loss of their digital photos, contacts, the illness of a pet, a family member, a breakup with a partner and more.

Across the board, the illness of a family member ranked in first place as the most distressing incident that they could experience. However, the loss or theft of a device ranked second place in multiple regions across the globe including the US, Japan, Russia, the UAE and APAC. In Europe, a breakup with a partner was ranked as second most distressing, but this was swiftly followed by the loss of all photos.

Although family members clearly take precedence in people’s hearts, the thought of losing some of the data stored on their digital devices is more distressing than the prospect of a car accident or a bad day at work (except in Japan), breaking up with a partner, a quarrel with a friend/ family member or partner, or even in some cases, a pet’s illness.

Highly valued but going cheap

Although people love their data — particularly their digital photos — and would evidently be distressed if they lost access to their digital memories, our study shows that people would also be prepared to sell their digital data for surprisingly little money. This was an unexpected finding of our experiment.

To assess the overall monetary value of personal data, participants in our experiment were asked how much they would pay for the recovery of all of their data should they lose it. Some said they would pay as little as 1 € and a very small number admitted they would pay as much as 5000 €. Removing the few (nine participants) that said they would pay 500 – 5000 €, the results show us that people would be willing to pay 74.73 € on average to recover all of the data on their smartphones.

However, when we delve into the results further, the value of data on people’s smartphones really comes to life. Photos of family and friends, contact information and personal documents were considered by participants of the experiment at the University of Wuerzburg to be the most important forms of data on their smartphones and participants were asked to give each of these data groups a monetary value. Interestingly, on average the category most money was distributed to was financial and payment details — valued at just 13.33 €. Contact information came second and was considered to be worth 11.89 € on average, while personal documents were third and considered to be worth 10.56 €. General photos were valued at 10.37 € on average, coming fourth place.

These are surprisingly low figures, considering the evident distress people admit they would experience if they were to lose their data.

Also surprisingly, the experiment shows us that it is people’s most precious memories which they are most likely to exchange for money. Participants were invited to be paid for the deletion of their data in our experiment — no data was actually deleted, but the process was simulated to give us reflective results. We found that photos of family and friends, personal documents and photos of the participants themselves, turned out to be the data categories most often approved for deletion — in exchange for the monetary value participants had previously attributed to these categories.

Considering our study shows us that people would be more distressed about the loss of their data than the prospect of a break up with their partner or a pet’s illness, perhaps the low monetary values attributed to data in our experiment should have partners and pets around the world concerned!

The experiment is showing us that there is a difference between emotional value and monetary value. Or, perhaps, despite people being aware that some types of data are more important to them than others, people have a low awareness of the value of their data. This is something that may explain why people are still not protecting their data effectively.

You only know what you love when it’s gone

Inviting participants to exchange data for money opened our eyes to a big question — do people really know how much they value their data until they’ve lost it? As expected, people said that the possibility of losing their most personally important data would be the most distressing of all data loss — 49% rated ‘private and sensitive photos and videos of myself’ as important and a high 18% said these are the most distressing to lose.

Yet data that is considered important isn’t always the most distressing data when lost. The prospect of losing their contact details is considered highly distressing for 14% of people, putting it in the top three most distressing types of data lost by people, despite contact details ranking much lower in terms of importance. In addition to this, a high 39% value private and sensitive photos of other people — such as their spouse — as important to them, but only 6% said they have found the loss of this data the most distressing. It is only when we’re faced with the prospect of losing — for example — our contacts, that we realise how important this data is to our daily lives, in comparison to photos of others, which are less distressing to lose than we may expect.

Our data loves and woes:

Data loss with a sweat

Surprises in how people deal with losing important data also emerged in our experiment. We monitored participants for electrodermal activity, nose tip temperatures and facial expressions when important data was lost, and found that people react physically when they believe their data has been lost — but perhaps not as strongly as we might have expected, again suggesting that the value people believe they place on their data does not always fully correspond with the real emotional value of that data.

Electrodermal activity (EDA) is related to activity in the nervous system and the skin’s sweat glands and is therefore often used in emotion research to measure fear responses. We measured participant reactions when they believed they had lost important data and saw higher EDA when the loss of more important personal data was simulated, compared to the loss of trivial data (M4.77 compared to M 3.90). At the same time, we were surprised to find that the difference was not as large as we expected.

Going cold with fear

Using an infrared thermal imaging system, we also measured the temperature of participants’ nose tips whilst simulating the loss of their important data. When distressed, constriction of the peripheral blood vessels reduces blood perfusion in people’s noses, so we expected to witness a dramatic temperature drop and indeed we did see a stronger thermal reaction when important data was lost.

Overall, the difference was interesting, with the average temperature increasing 0.07 Kelvin when the loss of important data was simulated, compared to 0.17 Kelvin when participants believed their trivial data was being lost.

Looking data loss in the face

The experiment also observed people’s facial expressions for indications of sadness when data loss was simulated. Here too, we can see that the loss of more important data lead to stronger expressions of sadness than the loss of trivial data. Systematic facial observations allowed research to draw conclusions about a participant’s emotional state through the automatic, computerised detection of sad expressions.

Yet, again, the difference between losing important and trivial data was not as large as we expected, leaving us asking — do people really know what type of data is more valuable to them until it’s lost? People may think they care about their data but these findings question that. Perhaps these findings go some way to explaining why people are still missing out on protecting their data.

Putting our valuable data in danger

The experiment and findings in the study have so far indicated that people would find the loss of their data more distressing than some other important life events, such as a breakup with their partner. But that they would be willing to put a price on their data, and be paid for its deletion.

People’s real emotional reactions to data are not always what they expect, and the reality of losing some data — contact details for example — is actually more stressful than losing photos of a spouse.

These ‘data value surprises’ leads us to question how people look after and protect their data — both the data they perceive to be precious and the data that is actually distressing to lose.

Our study questioned people’s opinions on what they thought posed the greatest risk to the safety and privacy of the information stored on their devices. We found that 73% correctly agreed that cybercriminals and hackers pose a high risk to their data, followed by malware (65%). This drops in the US, where only 61% of respondents said that cybercriminals posed a high risk to the privacy of data on their devices. In APAC, by contrast, 82% feel this is a concern.

Reckless behaviour may be putting people’s data in danger across the globe. For example, only 14% of Russians believe that when they are under the influence of alcohol, they put their data at high risk, while half of APAC respondents feel their data is at high risk in such a situation. That’s compared to 21% of people in the US, 22% of people in Europe and 46% of UAE residents.

High risks to data safety:

Hands off my device — and its soft skills

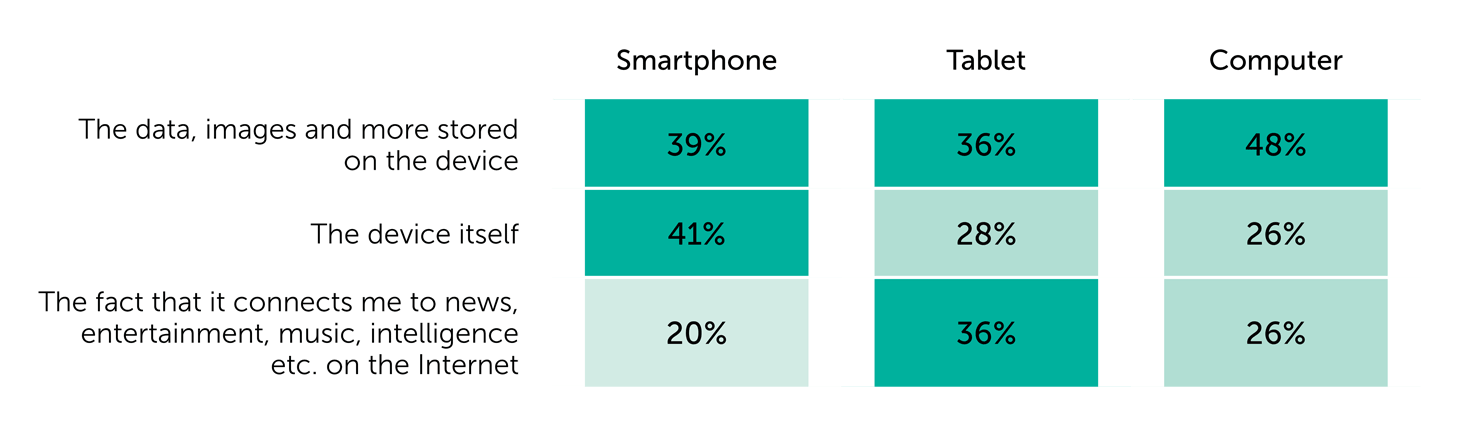

Many people also perceive high dangers to their information to be from physical threats — such as real-life criminals and thieves (65%). This concern corresponds with the value people place on their devices — for example, people tend to believe that their smartphone devices are as important as the data they carry — 41% said their smartphone itself was the most important element of this device compared to 39%, which said the data on their smartphone was more important.

Looking at other devices this value drops slightly — 28% that said their tablet itself was the most important and 26% that said the same for their computer. These devices are more likely to be valued for their soft skills. The survey tells us that 59% of people value their smartphones for their data and ability to connect with the outside world — including news, entertainment, music and all of the other joys of the Internet. But this feeling is even stronger for tablets (72%) and computers (74%), which value the ‘soft skills’ of their devices even more than the devices themselves.

What people consider to be the most valuable to them:

Taking unnecessary risks

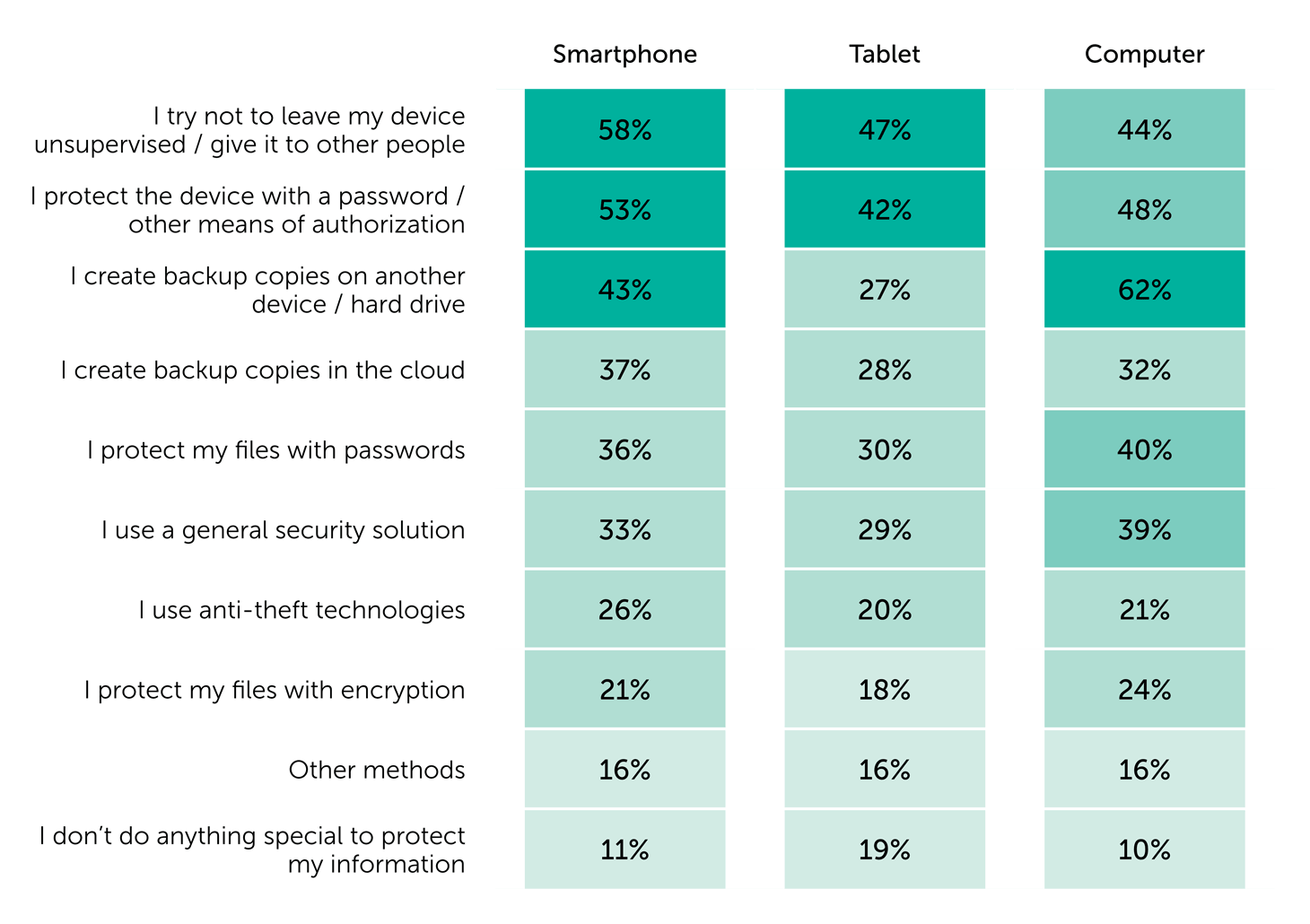

Yet despite using these devices to go online, people are not acting accordingly to protect their devices and data from the dangers of the Internet. Around half, for example, do not even use basic security measures such as passwords or PINs to protect their devices.

Aware but inactive

Despite an understanding of the high risk of cybercriminals and real-life criminals, we see that people do not protect their data properly, putting it even more at risk than they may expect.

The study shows a lack of awareness on how to effectively protect the data on their different devices. For example, most people (62%) create backup copies of the data stored on their computer but only two-fifths (43%) back up the data on their smartphones, despite these devices carrying so much important information. Only one-in-four people said they use anti-theft technologies on their smartphone, despite the fact that they would be extremely distressed by the loss of their smartphone, or the photos stored on it.

A worryingly low half still do not protect their devices with a password — this is 53% for smartphones, 42% for tablets and 48% for computers. Perhaps worse still, although the threat of cybercriminals and malware is considered by many to be the high risk to their data, only about a third have a security solution on their devices. This leaves them exposed to the dangers they are most afraid of. In addition, around one-in-ten people don’t do anything to protect their data at all (19% on tablets, 10% on computers and 11% on smartphones).

Measures taken to protect data:

Throwing caution into the winds

And against this backdrop of putting few measures in place to protect the precious data on their devices, people themselves are behaving carelessly — in reality, although people suspect cybercriminals to be a high risk to their data, people themselves are putting their data in danger.

Despite the fact that only 47% of people believe that their own inattentiveness can put their data safety at high risk, the second most popular reason people have lost their data in the past is because they have accidentally deleted it themselves (40% on smartphones, 36% on tablets and computers). This is second only to people losing data due to their device being damaged.

There is a discrepancy between the concerns people have about the safety of their data, and the measures they take (or rather don’t take) to protect that data.

Losing the data-risk gamble

If people are not correctly acknowledging how distressing it will be for them to lose the data they love, perhaps this goes some way to explaining why so many people risk losing their data by not protecting it effectively.

Supporting this statement, psychologists at the University of Wuerzburg have come to the following conclusions:

“Frequently, our decisions are rather heuristic and serve as mental short cuts. These heuristic decisions are often efficient and useful. However, they may also lead to inaccurate conclusions:

- We tend to ignore low-probability risks (“It is not true because I cannot imagine it might happen”).

- We cannot evaluate probabilities in an accurate manner (“1 in a 1 million is just as much as 1 in a billion”).

- Only if risks are imaginable and emotionally relevant, we will not ignore them (“I can image it and it is important for me personally. It must be risky!”).

Our study reveals that the risk of data loss seems to be perceived as a low-probability risk. Furthermore, participants have difficulties imagining that data loss might actually happen. Therefore, data loss is “not possible” and does not elicit strong emotional reactions. To assess these risks more properly and to avoid underestimation, people need a clearer understanding of what data loss means to them personally — regarding (1) the loss of emotionally relevant goods and (2) the functional principles of data loss. Both seem to be far from today’s average smartphone user’s knowledge.”

Instead of taking the appropriate measures and setting up the security precautions needed on their devices, people risk putting their data in danger. And they often lose the gamble. Our study shows us that around half or people have lost some data from their devices, including 51% that have lost data on their computers, 39% on their tablets and 56% on their smartphones. What’s worse, of the people who have lost data, only 16% have been able to recover all of it again and 53% has only been able to recover part of their data.

Photos and videos — the most valuable and irreplaceable forms of data — are most likely to be lost from smartphones. 44% of people have lost this data from their smartphones but fewer people have lost photos from their tablets (30%) or computers (37%).

If it is so easy for data to be lost forever, and if that data is precious and distressing to lose, it will become increasingly important for people to protect the data they love if they are to live safe and healthy lives online.

Conclusion

This report demonstrates the love people have for their data — but also the unnecessary risk that data is exposed to through lack of protection and carelessness.

We have seen that people’s memories are among the most precious of data stored on their connected devices, with many people reporting high levels of distress at the prospect of losing photos and videos of their children, their travels, their loved ones and themselves. In fact, the thought of losing some of the data stored on digital devices is more distressing for people than the prospect of a car accident, a bad day at work, breaking up with a partner, a quarrel with a friend/ family member or partner, or even a pet’s illness.

But there are contradictions in people’s behaviour. Although they seemingly have a deep affection for their data, and are aware of the prospect of cybercriminal and criminal activity which may put that data at risk, people are yet to truly value their data and effectively protect their devices from these dangers. In fact, many do not even protect their data from their own careless actions, yet alone the malicious intent of others.

At Kaspersky Lab, we see it as our mission to make the Internet a safer place for everyone to enjoy. We will therefore be using the findings of this report in our quest — to educate people on how to treat their precious data with more affection, and to help avoid the heartbreak of data loss.

In order to avoid data heartbreak and protect their precious data, users are advised to take the following six steps:

- Make backups of your data in the cloud — keep at least one copy of your precious data in a reliable cloud service accessible from any location around the world. This will enable you to restore your data as soon as you need it, wherever you are. Use two-factor authentication and data encryption for extra protection.

- Encrypt your most sensitive data — with specialized encryptors, such as DiskCryptor or Challenger, you can place your files in a reliable crypto-container that can only be accessed with a password. Kaspersky Total Security also contains encryption capabilities and users should also not overlook the data encryption tools incorporated in some operating systems (e.g. Encrypted File System in Microsoft Windows or Encryption in Google Android security settings).

- Have the power to destroy your data — to make sure that sensitive data on a lost or stolen device does not fall into the wrong hands, enable password protection on all of your devices, and use remote administration tools. For instance, with the help of the My Kaspersky portal you can remotely delete all personal files from your Android smartphone or tablet before others get their hands on them.

- Take passwords seriously — it is very important to use reliable passwords to all services and pages that you log in to, as well as to all your devices. If intruders brute force your password, they will gain access to the same information that you have access to, including your confidential files. Make sure you don’t use the same passwords for different sites, services and/or devices. If you do, when one site is compromised it opens up all the others.

- Use a security solution — to prevent your personal files from being destroyed, altered or stolen by malware, all users are strongly recommended to use an advanced online security solution. Chose a solution with an incorporated subsystem that can block network attacks, a software vulnerability control module, and the ability to track system processes for malicious activities in order to roll them back (such as ransomware’s encryption of files).

- Don’t panic! — even if your data has been accidentally deleted and you have no backups, all is not lost. Sometimes, data can be recovered using specialized software, such as the cross-platform TestDisk software. You can also ask trusted IT specialists for assistance.

For further information on Kaspersky Lab security solutions go to: https://www.kaspersky.com/home-security

research

research

Tips

Tips