Recently, English- and Russian-speaking people were attacked with a new ransomware Trojan called Ded Cryptor. It’s voracious, demanding a whopping 2 bitcoins (about $1,300) as ransom. Unfortunately, no decryption solution is available to restore files held hostage by Ded Cryptor.

When a computer is infected with Ded Cryptor, the malware changes the system wallpaper to a picture of an evil-looking Santa Claus. A scary image and a ransom demand — sounds like any other ransomware, right? But Ded Cryptor has a really interesting origin story, kind of a thriller, with good and bad guys battling it out, making mistakes, and facing consequences.

Ransomware for all!

It all started when Utku Sen, a security expert from Turkey, created a piece of ransomware and published the code online. Anybody could download it from GitHub, an open and free Web resource that developers use for collaborating on projects (the code was later removed; you’ll see why in a bit).

It was a rather revolutionary idea, making source code freely available to criminals, who would undoubtedly use it to make their own cryptors (and so they did). However, Sen, a white hat hacker, felt certain that every cybersecurity expert needs to understand how cybercriminals think — and how they code. He believed his unusual approach would help the good guys to oppose the bad guys more efficiently.

An earlier project, the Hidden Tear ransomware project, was also part of Sen’s experiment. From the very beginning, Sen’s work was meant for purposes of education and research. With time, he developed a new type of ransomware that could work offline. Later, EDA2 — a more powerful model — emerged.

EDA2 had better asymmetric encryption than Hidden Tear did. It also could communicate with a full-fledged command-and-control server, and it encrypted the key it transferred there. It also displayed a scary picture to the victim.

EDA2’s source code was also published on GitHub, which brought a lot of attention and criticism to Utku Sen — and not for nothing. With the source code freely available, wannabe cybercriminals who hadn’t even learned to code properly could use Sen’s open-source ransomware to relieve people of their money. Didn’t he understand that?

He did: Sen had inserted backdoors in his ransomware that enabled him to retrieve decryption keys. That means if he heard about his ransomware being exploited for malicious purposes, he could obtain the command-and-control server’s URL to extract the keys and give them to the victims. There was a problem, however. To decrypt their files, the victims needed to know about the white hat hacker and ask him for the keys. The vast majority of victims had never even heard of Utku Sen.

You made the ransomware, now pay the ransom!

Of course, third-party encryptors created with Hidden Tear and EDA2 source code were not long in coming. Sen dealt with the first one more or less successfully: He published the key and waited for victims to find it. But things did not go so well with the second cryptor.

Magic, ransomware that was based on EDA2, looked just like the original and promised to be nothing of interest. When Sen was informed about it, he tried to extract the decryption key as he had done before (through the backdoor) — but there was no way in. The cybercriminals using Magic had chosen a free host for their command-and-control server. When the hosting provider received complaints regarding the malicious activity, it simply deleted the criminals’ account and all of their files. Any chance of getting the encryption keys disappeared with the data.

The story doesn’t end there. The creators of Magic reached out to Utku Sen, and their conversation developed into a long and public discussion. They began by offering to publish the decryption key if Sen agreed to remove the EDA2 source code from the public domain and pay them 3 bitcoins. In time, both parties agreed to leave ransom out of the deal.

The negotiations turned out to be rather interesting: Readers learned about the hackers’ political motivation — and that they almost published the key when they heard from a man who lost all photos of his newborn son because of Magic.

In the end, Sen removed the EDA2 and Hidden Tear source code from GitHub, but he was too late; many people had already downloaded it. On February 2, 2016 Kaspersky Lab expert Jornt van der Wiel noted in an article on SecureList that there were 24 encryptors based on Hidden Tear and EDA2 in the wild. Since then the number has only increased.

How Ded Cryptor emerged

Ded Cryptor is one of those descendants. It uses EDA2 source code, but its command-and-control server is hosted in Tor for better security and anonymity. The ransomware communicates with the server over the tor2web service, which lets programs use Tor without a Tor browser.

In a way, Ded Cryptor, created from various pieces of open code published on GitHub, recalls Frankenstein’s monster. The creators borrowed code for the proxy server from another GitHub developer; and the code for sending requests was initially written by a third developer. An unusual aspect of the ransomware is that it doesn’t send requests to the server directly. Instead, it sets up a proxy server on the infected PC and uses that.

As far as we can tell, the Ded Cryptor developers are Russian speaking. First, the ransom note exists only in English and Russian. Second, Kaspersky Lab senior malware analyst Fedor Sinitsyn analyzed the ransomware code and found the file path C:UserssergeyDesktopдоделатьeda2-mastereda2eda2binReleaseOutputTrojanSkan.pdb. (By the way, the aforementioned Magic ransomware was also developed by Russian-speaking people.)

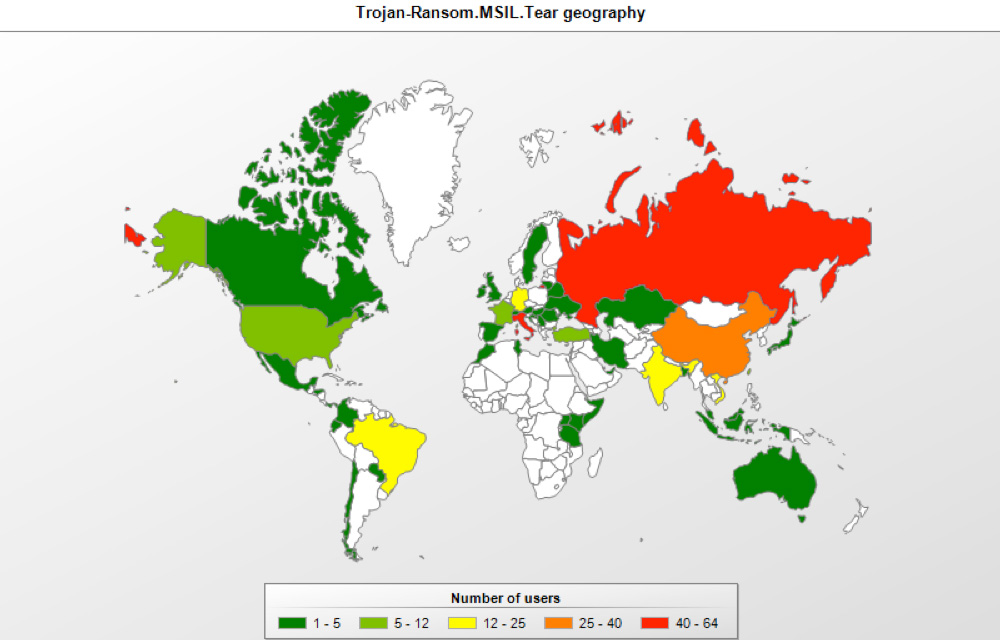

Unfortunately, little is known about how DedCryptor spreads. According to the Kaspersky Security Network, the EDA2-based ransomware is active mostly in Russia. Next come China, Germany, Vietnam, and India.

Also unfortunately, there is no available way to decrypt files maimed by Ded Cryptor. Victims can try to recover the data from shadow copies the operating system may have made. But the best protection is proactive — it’s much easier to prevent infection than deal with consequences.

Kaspersky Internet Security detects all Trojans based on Hidden Tear and EDA2 and warns users when it encounters Trojan-Ransom.MSIL.Tear. It also blocks ransomware operations and does not allow them to encrypt files.

Kaspersky Total Security does all that plus automates backups, which can be useful in all sorts of cases, from ransomware infection to sudden hard-drive death.

Ransomware

Ransomware

Tips

Tips