Yesterday marked the 10 year anniversary of the first smartphone malware being discovered. Today, Cabir worm looks harmless: it doesn’t steal money or passwords, nor does it delete users’ data. But it drains the battery within 2-3 hours – which was unseemly in 2004, but now, in 2014, it’s quite possible.

Today we will tell you how we discovered this virus, the origin of its’ name, what happened next and how it all ended. As a matter of act, the story has ended for some characters: e.g. for Symbian platform. For the rest of them – for smartphone manufacturers, users and for cybercrminals this is just the beginning.

Story One. It all happens by the end of the day.

Most IT people know the story well: servers crash, software bugs announce themselves aloud, new viruses drift in – all strictly at 6:30pm. On Fridays, mostly. In June 2004 everything happened – not on Friday, but – indeed by the end of the malware analysts’ shift. So they sent a file that had just dropped into their “virus” e-mail to the next shift, tagging it as “something weird”.

Today Cabir worm looks harmless: it doesn’t steal or delete anything.

Tweet

It became clear later, that the mysterious file had been sent over to many antivirus vendors. Most of them, however, contented themselves with the fact that it wasn’t Windows executable and thus it posed no threat to common PCs. Kaspersky Lab’s analyst Roman Kuzmenko who had just stepped up for the shift, quickly figured out it was an ARM program for Symbian platform that was just two years old at the time.

While the file analysis was still ongoing, a full-blown search operation unfolded all across Kaspersky Lab: we were looking for Symbian phones. It was not an easy task: at that time smartphones were quite a novelty, and a pretty expensive one (the first of them, Nokia 7650 came with a price tag of 600 euro).

While we were still searching for a smartphone (according to legend, people were even sent to the nearest electronics store in order to find one) it had become clear that a single smartphone wasn’t going to be enough. At least two were required, in order to confirm that the worm was capable of spreading via Bluetooth on its own. Kudos to Roman Kuzmenko: he conducted the analysis of an entirely new program for an underexplored platform very quickly, and predicted its key features way before it’d been launched on real devices.

Six months prior Alexander Gostev summed up the year 2003 and predicted that the mobile malware will emerge promptly. He was right.

Story Two. Why “Cabir”?

Actually almost all malware are named by their (mostly) anonymous authors. We could just pick the filename – Caribe.sis. However there is a tacit agreement between the antivirus vendors not to do it this way. First, the same malware can be distributed under the different names (but the classification should be preserved). Second, we shouldn’t encourage virus writers promoting their own names: some of these miscreants breed pests just to extort their five minutes of glory from antimalware vendors.

In most cases, however, the final name is actually related to virus writers’ creative whim – this or that way. So happened with Cabir, but it wasn’t just about swapping letters. During the peak of the arguments regarding the first smartphone worm, Elena Kabirova, Kaspersky Lab’s employee, entered the lab. Upon seeing her, Eugene Kaspersky offered to call the worm after her name, due to obvious resemblance, to which she graciously agreed (but not until making sure that the event itself was significant indeed).

Story Three. The iron room and the collection of devices.

So, the first worm for the smartphones had been successfully discovered. The world found out that not all files sent in are useful, and that the viruses can be distributed not just via Internet and/or flashdrives, but also over the air, just like the common flu. Despite the fact that Cabir was only translatable via Bluetooth and could infect only the phones within 10 meters range, it was still accounted for a couple of epidemics. Most often it manifested itself in crowded areas: for instance a wave of infections rolled all over the stadium in Helsinki during the 2005 World Championships in Athletics. Moreover, one could get a message with a malicious attachment anywhere in the subway. Cabir owes its relative “popularity” to the well-known group of distinguished gentlemen codenamed 29A. So we have as many as 18 variants of this worm in our base. They are almost identical, although Cabir.k dated April 2005 could use MMS (do you remember them?) to spread itself, causing a user quite real monetary damage.

And what about iron room? Researching new variants of Cabir (and similar malware) caused local incidents within Kaspersky Lab. Just imagine: a virus analyst launches a new malware variant on a test smartphone, while a level below a mobile antivirus developer suddenly receives an offer to accept a file. So we needed a confined space for experimenting, and so the room where neither cellular, nor WiFi signal could pervade, and where we could chill out test new viruses without risking to infect our colleagues’ phones.

Thanks to Cabir, we’ve acquired a constantly renewed collection of mobile devices. Nokia 3650 was the first one:

Other than a dubious honor to be the second Nokia smartphone, it’s remembered for its remarkably unhandy keyboard.

Nokia N-Gage was there too:

A possibility to play mobile games ( quite good for that time) was a big advantage for this device. On the contrary, when used as a phone it had to be apposed to the ear with its side-edge, where both speaker and microphone were located; a user then looked like some kind of Van Gogh Elephant.

Story Four. Not just Bluetooth.

The method of spreading via Bluetooth itself was quite original, but short-lived. First came smartphone malware spreading itself via MMS using the devices contact lists. It was followed by a long-running epidemic of SMS sent to the paid numbers (which brought criminals a good deal of income), and then all of the malicious activity had gone to the Web – faster, more reliable, no limits on damage range.

So that fabulous “iron room” was our experts favorite meditation place for a limited time. While moving to a new office, we abandoned it – there was no reason to bring it along.

There was, however, one exception: Flame, an extremely complex cyber-espionage tool discovered in 2012. Its Bluetooth functionality isn’t the main one, but it has some interesting capabilities. First, it gathers data on the devices in range (the same way you can find out the smart-TV model in the neighboring apartment). Second, Flame can turn the Bluetooth unit into a sort of a beacon indicating that an infected PC is nearby – for someone who knows.

Story Five. Rise and Fall of Symbian malware and the dawn of the glorious (?!) future

During the entire history of monitoring, Kaspersky Lab detected 621 malware variants for Symbian – all of them differing from each other in something more than just name and icon. Not many, to be honest. Until mid-2008 all new items produced by cybercriminals (and amateur virus writers too) were targeting Symbian smartphones alone. Then the tide turned. First, Nokia as the primary Symbian manufacturer started taking measures. For instance, digital signatures were introduced (many people can still recall how much headache they caused). Then suddenly it became clear that writing malware for platform-independent Java ME was much more lucrative. Java malware potentially threatens a lot more people – users of the common phones. Smartphones were endangered too – at least those with Java support. A double impact!

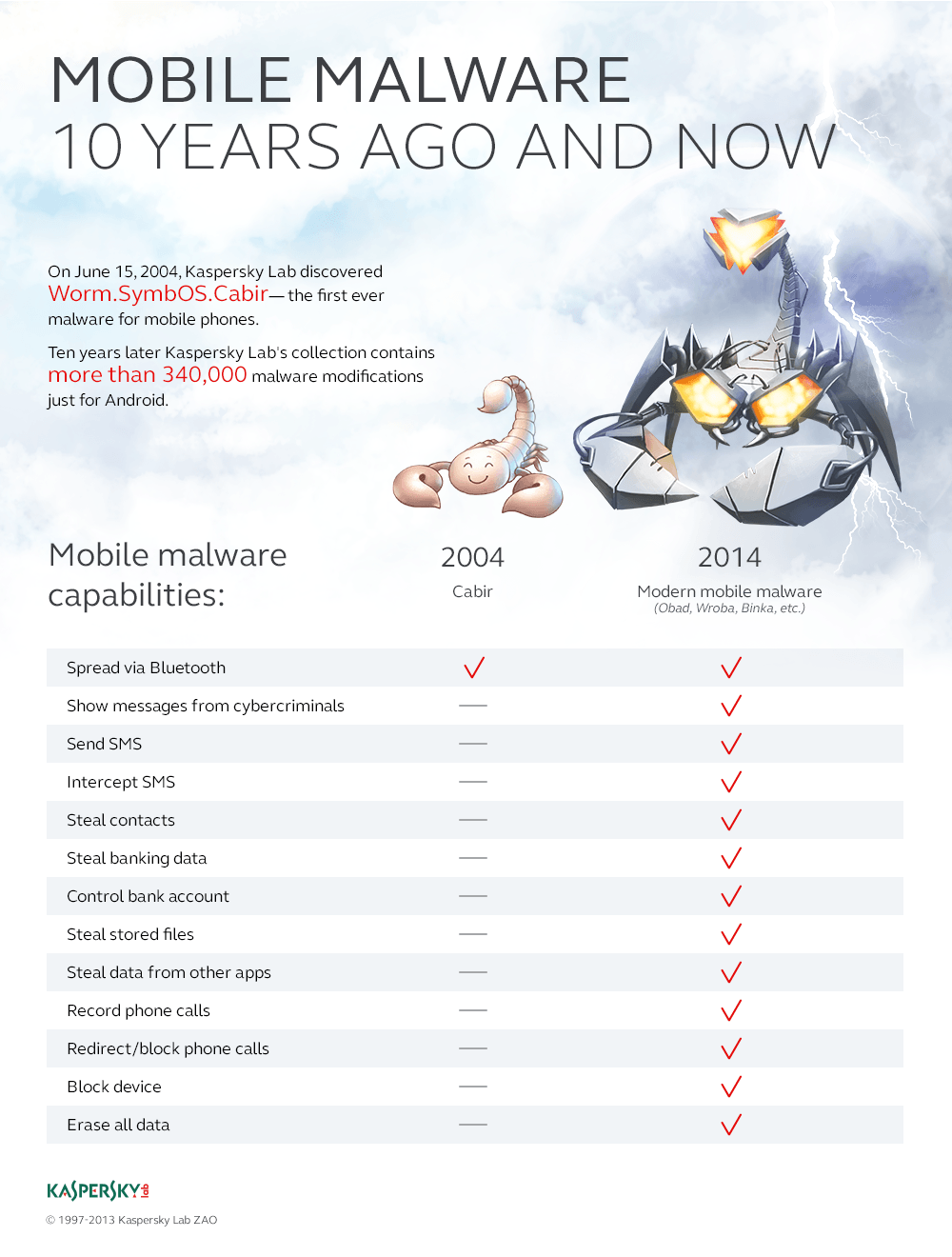

In August 2010 our base received the first entry describing a malicious program for Android OS. It is now a primary target for the cybercriminals: so far we have about 370 thousand malware variants for this platform. Compare this to the pathetic hundreds for Symbian.

Suddenly it became clear that writing malware for Java ME is much more lucrative.

Tweet

The last Symbian phone had been released in 2012. For weal or for woe, this platform is dead now. While Cabir was the first malware for Nokia smartphones, what was the last one? They still emerge from time to time now. The last more or less unique one had been discovered on May 6th, 2014 – a rather plain SMS Trojan, sending out messages to paid numbers and concealing the delivery notifications from the user. By the way, it’s been 8 months between the discovery of this Trojan and the previous malware.

But it is all just the beginning for the mobile devices. Although during the first two years after Cabir discovery there weren’t many mobile viruses, they were advancing rapidly. Over two years they have passed all the stages – viruses to Trojans to backdoors, etc. – that took PC malware more than a decade to pass. For the last 10 years mobile malware “learned” how to steal money and passwords, how to crack the online banking, how to intercept the SMS with one-time passwords, and – the most recent development – how to encrypt users’ data and then extort money for decryption. We are yet to see what comes next. But, for now, it’s clear how harmless the “firstling” was. Created by the altruistic malware writers just for the sake of an art, it encroached on the battery alone, not the user’s money. A funny creature from the day before yesterday – when the smartphones were multiple, different and had physical buttons.

And you? Have you met Cabir?

Cabir

Cabir

Tips

Tips